Alpenglow Design Process

3. Play Testing

Applying game theory to the process of designing a game is a great way to keep the project on task as anything is subject to change.

Creating balance is a theme that has come up over and over for me as Alpenglow came together. A great game of any complexity has good balance so you don't notice its impact on game play however you can easily identify when something is too powerful (or weak). Those situations are cause for unhappy players on one hand, and have a big impact on gameplay and the ultimate goals on the other. I read a bit on game theory and drew on my research in complexity theory and city design to establish that initial spread of where values, resources and goals would come together. In the end though, you can't balance a game without play-testing.

We Made a Game!

It wasn't until the third or fourth play test that we had all of the parts put together. It really took that time to even iron out game play flow and rules, sometimes we would only make it one round before making changes and simply starting over. It is funny how that worked because most of the play testers were thinking along the same lines as we played. We all started to develop a shared vision for it's direction and really harnessed the variety of ideas from different minds.

The first prototype was actually a shared set of components for two separate games. We played both before they started to come together. It was a funny process actually when hauling 1.5 games across the country for the holidays, the family asking how the game is going and asking, "which one?". As we played the two, it really came together as one game, seeing how each had a really solid mechanism that the other was missing. The goal was to keep it simple and easy to learn and play but it was much better and more fun together.

Wireframes and Feedback Loops

One of the most frequent questions from play testers was about game art. I tried pretty hard not to work on game art as I figured we would get there eventually. From even the first sketches, I kept it to a basic wireframe and that worked pretty well. My friends and family played it without issue and the wireframe look really made it feel like it was a work in progress, a game that was still open to feedback no matter how big or small. This helped in 3 ways for us. First, we didn't need to delay play testing for the sake of art or illustrations. Hacking together a box of components goes faster this way. Second, With art out of the way, the players focused more on function, flow, rules, and the game mechanics. This is invaluable and what I wanted to discuss with them. Third, you aren't stuck with game components that are hacked together. Need to make a value change to a card? Just cross it off and write the new value. Want to change the board while playing? Break out the markers. It's a working document and we enjoyed pushing and pulling for a better experience and product in the end.

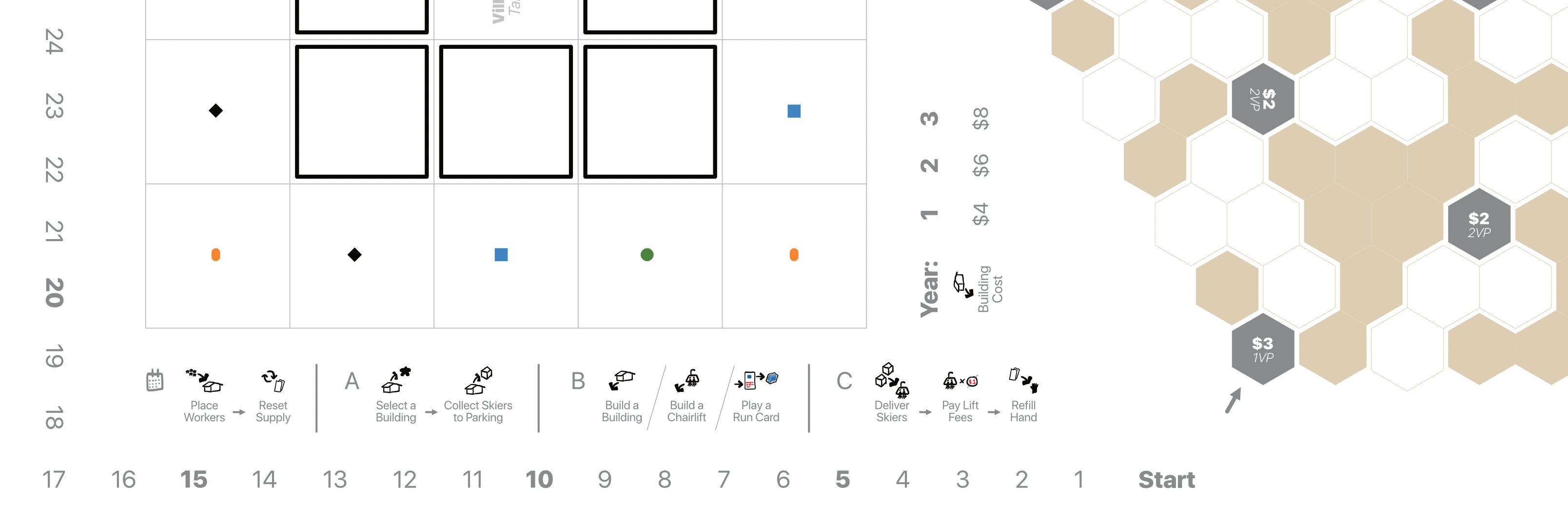

The wireframes also allowed me to take a step back and not worry about sizes, shapes, and other details before the flow and mechanics were even settled. It was funny how depending on the game and rules we had, scores would be in the 20-30 range or in the 150-200 range. No need to dwell on the scoring track yet.

The last thing was the ability to simply record feedback on the game itself. My notes and player feedback simply adorned each version. Once we collected a critical mass of feedback, a new version would be prepared.

Versions

Versioning didn't become a factor until a second copy was put together. We had a request to send a copy to my family so having a version on it allowed me to track changes and send over new updates as they came up. It also marked a new phase in preparing updates to the board and components - the computer. I opened up Affinity Publisher and made the first board there. Brought in a grid and started building out the components digitally. It meant I was feeling like the rules were starting to become settled and it was a way to think about the game in a different way.

Over the course of play-testing, I had amassed some 20 unique versions of the game but they really represented that many rounds of feedback and drawing board time before it was ready for testing again. It's not that the game changed that many times as much as it was small variations and explorations. Think tweaks to address core nuggets of feedback.

Changing the Rules as You Play

The best part of play testing was the discovery of better ideas and diversion from the master idea of the game in my head. When I think about something for too long, I struggle to think clearly about it. Dreaming up a game is no different. Being willing to change things was tough but necessary and truly made the game what it is today. An great example of this comes from just about every play tester in the early days.

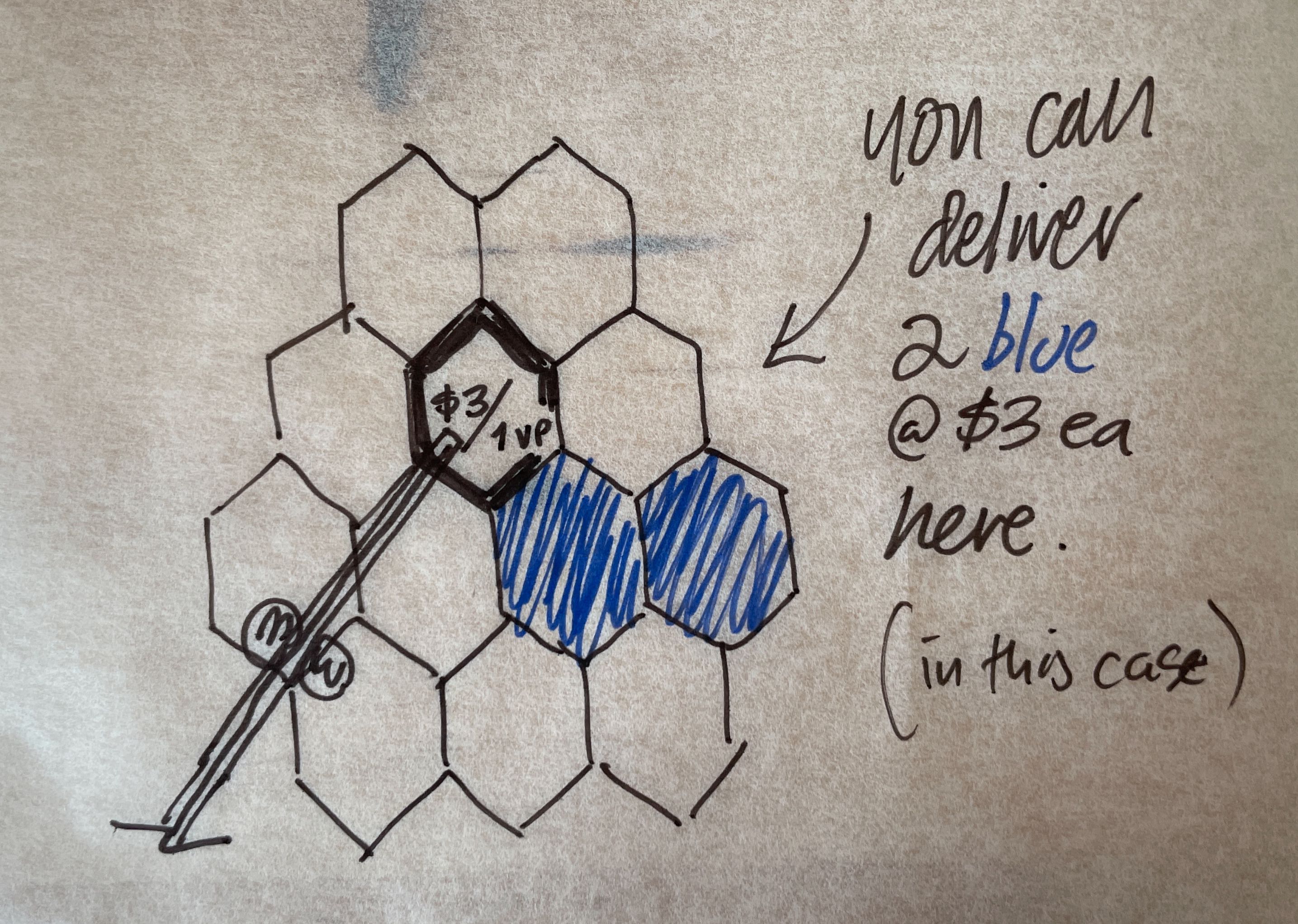

My brother commented on how there was a lack of places to deliver skiers, and that the mountain was a patchwork of run tiles. Real ski resorts have long runs of single difficulty from top to bottom so the game should account for that. The combination naturally presented a solution. Daisy-chain run tiles of like difficulty/color and you can deliver more skiers. We would sketch out the rule, often on tracing paper and then it would be set in stone.

Same happened with our friend Marcie who commented on the the imbalance of revenue and victory points. We originally had money be the income from delivering skiers to run tiles but that yielded too much money and shortened the game. It questioned where victory points should come from, or at all (thinking of Pipeline and how it is the resource used to buy everything else, and the way you win at the end). Her suggestion to offer a choice of victory points or money for a skier changed everything about the dynamics and balanced out the points and funds throughout play.

We had countless moments of feedback like this and that was what made the game really come together. Game designers and reviewers all talk about the power of play-testing and it is really understated. It was simply fun to play the game as well so it's not as much work as you would think.

Challenges

As we played the game a number of hurdles and bumps continued to present themselves. Some were the product of overthinking or questioning if we were on the right path, and others were a matter of logistics or lack of completeness.

We would always have the ski game when visiting friends for a game night but sometimes would question if it was the game to play because of complexity (not everyone is up to learn a new game or play heavy Euro games for that matter) or completeness. Every time the game is opened up, the players would be judging the game. Small things not yet fixed become blemishes, the lack of art makes it feel a little less engaging (Jamie Stegmaier talks about hooks and how art can be one), and sometimes people just don't like the game. We also ran into issues with the rules, and lack of a rulebook. I don't know when you should sit down and write out rules but we didn't for a while. It came back to bite us when we'd forget rule changes and would have to re-invent on the fly.

All in all, the challenges were valuable because it is what we are up against if Alpenglow is to be mass produced and put out there for anyone to play. We started to better understand how people learn games and how to craft player aids that make more sense. We learned how to teach the game in a way that left the strategy to the players. We also learned how to play the game as many different ways as we could.

Play testing was also a delight. The ability to see people entering into your world and trying to figure out a puzzle you crafted is a special feeling. Watching people figure out the mechanics, understand why things were done the way we had it, and become surprised when someone found a loophole or imbalance that almost ensured a win or loss. Spontaneity was the theme of Alpenglow for a year.

Strategy

The most interesting part of the whole process was the concept of strategy. When you learn a new game, you often establish a strategy and revise as needed to push for a win. After playing a few times, you'll have a go-to rhythm, and ways to react to the styles and strategies of the other players. When designing the game, I always had an idea of how people would play and always looked for the other ways people could play.

Thinking of Great Western Trail, most will suggest that you play a combination of cowboys, buildings, and the engineers where you make even progress across all fronts. Much has been written on strategy for the game but one path I found very exciting was the deck shredding strategy which is available due to a single auxiliary action made available. I'd guess most players never even make it available let alone use it but it's such a fun challenge. With the expansion, that action comes out front and center as a viable means to compete and that is such a fun way to think about a game. First, the game differs based on the starting setup, but to have an action that opens up a new way of playing.

With work, covid, and life keeping us busy, I spent a decent part of a year thinking about what are new ways people can play Alpenglow without making structural changes. Part of this is rooted in making the game more balanced yet varied for players. Games I love are ones that have a variety of ways to get points so that an unlucky initial draw doesn't kill your chances. It also means you find yourself focused on developing better strategies rather than relying on luck.

Alpenglow offers a variety of ways to get points and play testing opened up the ways we could take advantage of new ways of playing. My brother in law always plays the game with the most unique approaches. Sometimes due to the lack of experience with the game or other strategies, and sometimes following his more player-vs-player tendencies at the dinner table.

An example of a strategy he tried was to play defense on the mountain. By building a ton of chairlifts, he locked the other players out of the most lucrative victory point generators but in doing so pushed himself into a corner. This was an opportunity to evaluate balance of points, costs, and actions in realtime. The cost of running chairlifts was prohibitively high but it prevented the typical large point grabs the rest of us were used to later in the game. We revised the values and even introduced a goal card to promote behavior like this.

The same thing happened with the strategy to gain most of your points from buildings. With a fixed number of lots on the board, one who focuses on buildings will get cheap points and income between turns. Buildings become expensive though and when you only have 15 turns in total, it takes away from other opportunities to get points and compete. We also worked to balance things out to allow this path.

To Add, or not to Add

As I play and learn about new games with unique mechanics, components, and strategies, I always think back to Alpenglow and how they could be introduced. Games in general are amazing in the diversity of ways to engage, scheme, and to have fun and it can be hard not to pick and choose mechanism or components that could be a good addition.

We always looked at the theme as a source of the game's major elements, relationships, and overall flow and it was hard to keep things simple. Modern dynamics with ski areas offering season passes, creating alliances, and changing the ethos of skiing from the jet setting quiet mountain adventure experience to the ski industrial complex and sprawling year round resort regions offers much to draw from for Alpenglow, while giving us options as to how we wanted our vision of it to be.

We stray away from the alliances and passes in Alpenglow except for a few card actions (Partner Resort lets you use another player's chairlifts for a shared income) but are keeping this in our back pocket for expansions. Parks is a great example of a game centered on the rich heritage of and action of exploring the outdoors of the national parks. Granted, it was an excuse to put the amazing art to good use in board game format, they didn't get hung up on the dynamics of travel or how national parks operate. They kept that in the meta, you go hiking and visit parks. Easy. Alpenglow is a step beyond that but still gives the pioneering spirit of making your own ski area and optimizing growth.

One way we did grow the game though was in ways to address balance, strategy, flow, variety, and general delight. Any new element that contributed in multiple ways would be tested. The start of a game can be daunting or simply confusing when you have a handful of actions to choose from and you have no idea what you are doing. We added goal cards to assist in this endeavor. Players have a stragety laid out for them and are given an idea of where to begin.

Blind Testing and Rules

As the game came together and everything started to settle, we started to push our boundaries and tried playing with more people. Blind play testing and a rulebook was a big part in this. Version 9 marked a one-page set of rules that walks through gameplay. While most was covered, it was a start and we had a few groups pick it up without intervention. Sitting back and holding my tongue was super hard but very valuable.

Removing myself from the game was akin to removing a crutch or training wheels. My ability to teach was inseparable from my way of playing and the game continued to improve as the rules developed and people played on their own. It also meant that on-the-fly ideation was a thing of the past but the game had matured to get to this point.

Writing the rules also felt like the process of building the first prototype. What to include, how to craft the language, and what examples should be shown. I dive into the rulebook in a future article but I want to touch on the point that the rules become a core component I shouldn't have overlooked. You can wait until things settle down but they guide gameplay and adoption and that is a make-or-break moment for new players. We have all played a game where one didn't share all of the rules until too late, or a rulebook was missing or poorly written.

Art

The last thing to touch on is art. Play testing was more than mechanics and gameplay. It also was a way to test out and solicit ideas for what this thing should look like. What kinds of graphics should be developed? Where should we substitute text for icons? What should the components be? All things that play testing helped with. I will also dive into art in another post.

All in all, play testing was invaluable for Alpenglow as much as it was fun. We collected feedback, broke things and proposed new solutions. Added elements and took them away. Continued to develop but also optimized. Ideas, sketches, complaints, and dozens of half-played games all come together to make the game. We had a great time playing and my friends loved the power of proposing new rules and changes. It's not every day you can change the rules of the game as you play.

Photo Credit and Caption: Alpenglow Game Board by Sean Wittmeyer

Cite this page:

Wittmeyer, S. (2022, 23 December). 3. Play Testing. Retrieved from https://seanwittmeyer.com/definition/alpenglow-play-testing

3. Play Testing was updated December 23rd, 2022.